Episode 6: The Axmouth to Lyme Regis Undercliffs National Nature Reserve

“90% of nature conservation, certainly in this county, is about arresting ecological succession. That’s all its about, it’s about stopping the habitat developing.”

Ever since moving to Dorset in 2004, I have had a fascination with “the Undercliffs”, an incredible seven mile National Nature Reserve of vegetated landslips, cliffs, hidden pinnacles, ponds, springs, patches of chalk grassland, and remote beaches between Lyme Regis and Axmouth on the East Devon Coast.

But why - I hear you ask - am I covering this here? Well, first off it was because I thought it was one of the few ‘wild’ parts of southern England, and to some extent that is still true, so I thought I should do a comparison between a rewilded landscape and a wild landscape.

However, as I got more involved in this project, I realised the Undercliffs is in fact a rewilded landscape and what is now largely forested landslide material and cliffs, was, less than 200 years ago, busy agricultural land. Also, although it is one of, if not the wildest areas along the south coast, it is not as wild as at first glance, as you will hear in the interviews.

The ivy, trailing clematis, Harts-tongue ferns and dense canopy make parts of the Undercliffs reminiscent of temperate rainforests

So the story being told here here is about what has happened to the nature of an area after agriculture ceased nearly two centuries ago, and how it has over recent years been increasingly managed by people once again. The difference, however, is that now it is managed for our pre-conceived - and very well meaning - notions of what is good for nature. Rather than starting with people, I will start with the place itself.

The Undercliffs

Location - East Devon, UK, between Lyme Regis and Axmouth / Seaton

3D map of the undercliffs © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap

This case study is not a comprehensive history of the reserve, it is just to give you a feel for it, and you can always find out more online here, here or numerous other sources. It is also a very difficult place to photograph well, with very little open vistas, a lot of vegetation and only one real path.

Drone shot of where the cliffs meet the sea - you can see the ongoing landslides creating new habitats for wildlife

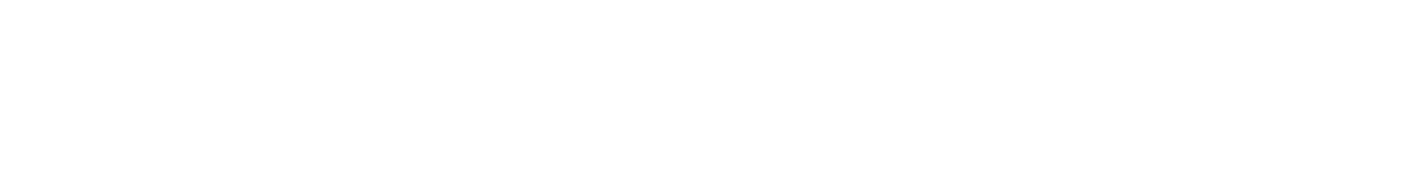

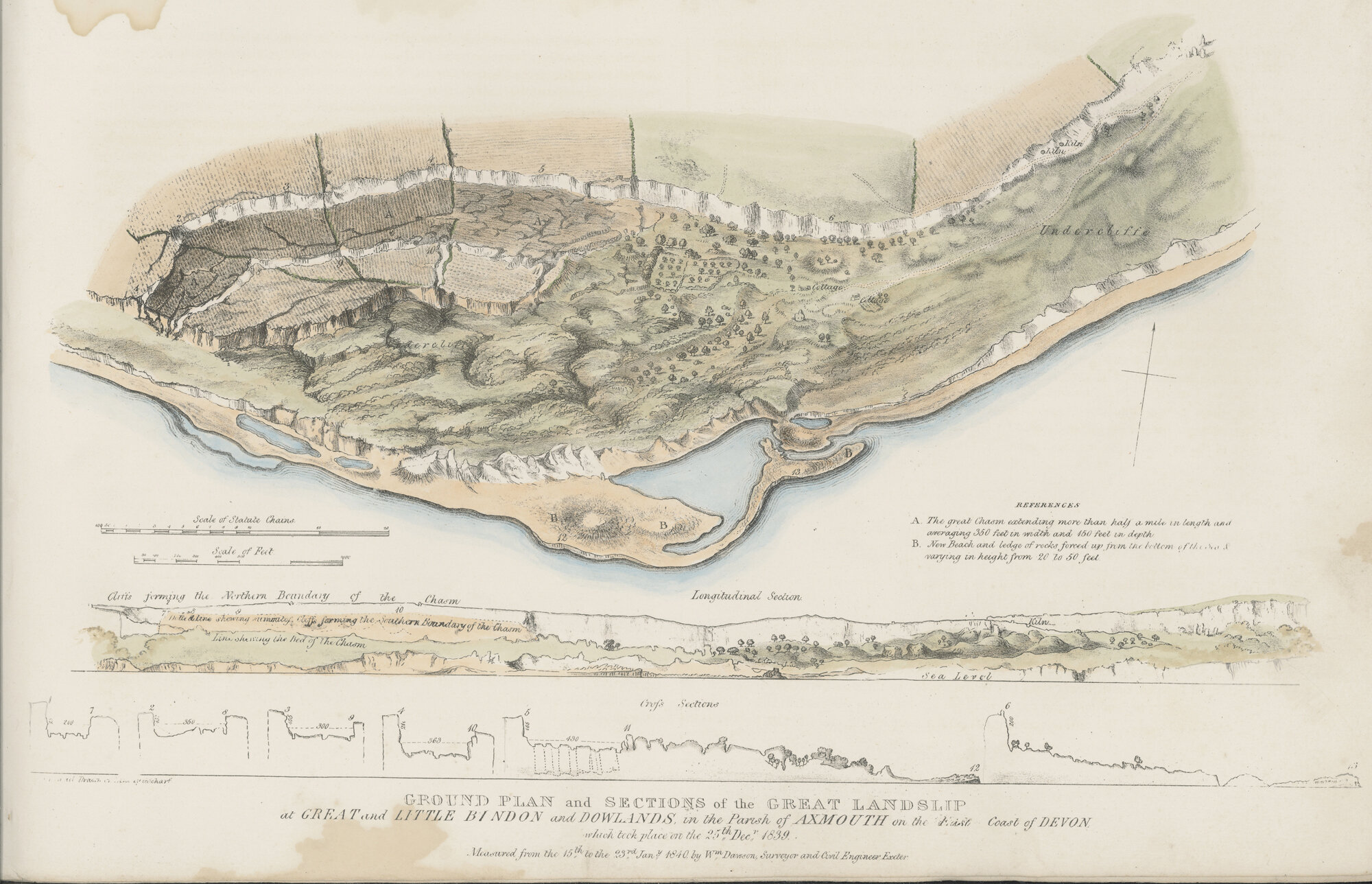

‘Undercliff’ means any land that is a terrace, or lower cliff area formed by a landslide. The Axmouth to Lyme Regis Undercliffs has had a succession of landslides dating back for many years which has led to the wild and diverse ecosystem that you can see today. Most notable was the Great, or Bindon Landslip of 1839, in which a vast area of former agricultural land slipped downwards, pushing a lot of material into the sea, and creating this vast landscape of bare rocks, chasms, broken fences, and even some destroyed properties. Anyone interested in this can find out more information on the Lyme Regis Museum website, but this landslide and the landscape it produced became a tourist phenomenon of the time, and also led to the first fully scientific report ever produced about a major landslip.

Images above used with kind permission of Lyme Regis Museum

So, put more simply, a huge chunk of cliff across a wide area fell into the sea overnight. Land moved, an island was formed, chasms were created and in this small part of Devon, it all turned a bit upside down. So the area that remained as so uneven in terrain that it was no longer any use for agriculture and was almost entirely left to nature.

The result is a stretch of coast with an incredible mosaic of micro-habitats within a dominant climax Ash woodland community, but interspersed with areas of chalk grassland and other interesting vegetation communities. It does have some areas of Sycamore and Beech, planted by one of the landowners for commercial purposes, but never exploited because of the huge difficulties in extracting the wood.

To walk through it feels like walking though nowhere else England. It is lush and verdant, with Hart’s Tongue ferns and horsetails, and feels very jungle-like with clematis ‘lianas’ dangling down tempting you to swing from tree to tree, and ivy enwrapping whole trees like the strangler figs of tropical forests.

If you time the season, you can see numerous different type of orchid on the small areas of chalk grassland, or wild daffodils, and if you find the right path – something I don’t recommend without a guide, you can find your way to unexplored and secluded bays with boulder fields akin to those in the Rockies brought to fame by Ansel Adams.

Boulder strewn beach looking towards Lyme Regis

The beaches and the geology are important, but it is the plants that dominate the reserve, and that have developed - and continue to develop - since the agricultural use in the 1800s. With the plant life and the huge variety of habitats comes a mass of invertebrates, which in itself brings in the birds, bats and insectivorous mammals like shrews. Click on any of the following images to enlarge.

Part of the amazing variety of life found in the Undercliffs.

My personal favourite plant in the world - the Bee orchid

I love the place – I love its dampness and greenery, I love the fact that sometimes you can rise above that and see the sea, I love the isolation and the fact that there is only really one way in and one way out. But for nature it leaves me with a conundrum. You could say that it is a rewilded area – the signs of the original agriculture are limited to a few Devon banks and a sheepwash - and with almost no intervention. Is it perhaps the definitive response to “What if you just leave it?”…?

Perhaps not. Since 1955 it has been a National Nature Reserve (NNR) and as Tom Sunderland says in the interview it is important for wildlife, geology, geomorphology, literature, culture and other things – it is an amazingly diverse place.

So as you will know by now my stories always involve people, and there are three people involved in the story, Tom Sunderland - NNR Manager, Rob Beard - Reserve Warden, and Donald Campbell OBE - volunteer and Undercliffs expert. The link to the podcast is here, and you can find out more about these guys below.

Tom

Tom Sunderland, National Nature Reserve manager for Natural England, and man at home with his hat. I have know Tom for more than 10 years, and many years prior we had shared the same Ecology mentor at Leeds University without knowing each other. Tom is a true naturalist, but also a pragmatist who understands well that to make gains for nature in today’s world you need to work with nature and work with the system. Tom is the (Senior) Reserve Manager but doesn’t like the title Senior.

Rob

Rob Beard, is a hero with a brushcutter! I only met Rob in 2020, but warmed to him straight away, especially when he put up with odd requests for a “hero pose” with burning brush in the background. Rob is the reserve warden and also works for Natural England. The interview goes into more detail about what he is doing here and why.

Donald

Donald Campbell is a volunteer who awarded an OBE a few years back for his services to nature conservation, particularly with regards to his work on the Undercliffs. He proudly keeps his framed certificate in the downstairs loo, and what he doesn’t know about the Undercliffs is clearly not worth knowing. Donald has taken me on many ‘off-piste’ walks through the reserve, and on at least one, we have not been lost (for very long). He is a gent, and a great source of knowledge and opinions, and he loves his dog Fuggles and the Undercliffs in equal measure.

My interview with Donald is below - it lasts about 35 mins. Please do have a listen, Donald has some great stuff to say.

Management

So all three of the above people are important for the reserve, but in different ways. There are, of course, many others involved, particularly the other volunteers who help keep the paths passable, do the annual cut and rake on goat island, and go out with mist nets or moth traps to see what lives there. But their role is critical in helping to manage it, and tell people about it.

As an NNR, the area it is subject to ‘management’, the main activities for which – in terms of the biodiversity - are to support the chalk grasslands, the removal of the ‘dreaded’ Buddleia from some of the more open areas, and the extraction of the also non-native Laurel and Rhododendrons from within a few parts of the woodland. I will concentrate on the chalk grassland and Buddleia.

The majority of the UK’s chalk grassland has been ‘improved’ for agricultural means, so areas that are allowed to be natural are few and far between. However, great though is for certain – often charismatic – plant and insect species such as bird’s foot trefoil, small scabious, various orchids and the Adonis Blue butterfly, it is not a climax vegetation community and is only maintained by intervention from people or from natural disturbance.

One of the annually ‘cut and raked’ patches of chalk grassland dotted throughout the reserve

Drone shot of ‘Goat Island’ (no-one knows why it is called this), the largest area of managed chalk grassland in the reserve.

The chalk grasslands are abundant with wild flowers, including Pyramidal orchids.

The dreaded Buddleia is also another conundrum. It is a non-native invasive, which means it is an introduced species, but it is naturalised, so very widespread. It is, however, pretty vicious, and given the right conditions, particular disturbed stony ground, it will muscle out all of the native species in a bid to take over, and it is very effective at that. So it is taken out of the Undercliffs in places so that the native species can colonise in its place.

This was where I caught up with Rob on a mission to cut back the Buddleia, and you can see from the following photos that far from the idyllic gentle grazing and browsing of large herbivores, it is the short sharp approach with brush cutters and chainsaws, and slightly post-apocalyptic scenes!

Buddleia

So indulge me a slight digression… I am not going to delve into the ins and outs of what to do with Buddleia - please listen to Rob talking on the podcast for that - but photographically, you can look at this plant very differently. Although ostensibly one of the bad guys, it is much loved by some gardeners and is a superb long-season source of nectar, so I figured I would give it the make-over with a VIP studio treatment. See what you think. This is purely an exercise in photography and not in nature conservation, but I think it is helpful to look at the things we don’t like in different ways as, once they are gone, we may just miss them.

Looking further - looking for art in nature - the following three photos are of old Buddleia tree stumps taken near where Rob was working on the latest round of clearances, and I think they are beautiful. As ever - click the images to enlarge.

So as to make sure you don’t think I am encouraging an alien invasive, the RSPB has some great advice about Buddleia here.

Back to management and rewilding

We often use word ‘intervention’ in respect of managing nature, and in some cases we may mean herbivores, but in this case we mean people using mowers, brush cutters, chainsaws, scythes and other tools. We are the ecosystem engineers in this case although I do raise the question in the interviews about whether herbivores might be introduced.

So to maintain this NNR in ‘favourable condition’ the grasslands are cut and raked, the Buddleia is kept from taking over, and a few other small scale interventions are done by the team. The other main job they do is visitor management, particularly keeping the South West Coast Path National Trail that runs through it in good condition, and re-routing the trail when another landslide takes the path out. It is, after all, the only way in, and the only way out, and was closed for 5 years this decade because of a major fall.

In terms of rewilding, well, this is a largely rewilded area, having recovered from agriculture over nearly 200 years, and due to the comparative lack of native free roaming herbivores that could have impacted on it (the deer population is pretty small), has reverted to a largely Ash climax woodland. Donald thinks that 90% of it is untouched, and with such difficult terrain and only one main path, I am minded to agree. Certainly, the biodiversity of the area is very high and very special. Interestingly a lot of the early to mid-succession areas that have formed because of the landslips are dominated by brambles, blackthorn, hawthorn and other key species that are seen at rewilding sites like Knepp (to follow).

“The underclifs absolutely smashes every other bioblitz Ive seen in terms of number of species”

The following two images shows the drawing made of The Chasm and Goat Island in 1839 directly after the great landslide, and a similar drone shot now in which you can just make out the Island and the deep Chasm - now fully wooded.. I will try to get a better comparison shot when I can.

So some parts are now managed to provide islands of very specific habitats, and this is no bad thing, given how little chalk grassland is left, but it is in a balance between man and nature, something that I think Tom reflects well in his interview.

“It is the best self-sown ash woodland in the country”

I went into this thinking it is a Wild area of southern England - but is it wild? Well using one definition of wild: “uninhabited, uncultivated, or inhospitable.” then yup, it pretty much fits that bill, even on the main path it is not an easy walk. However, Seaton (popn 8,000) is just around the corner, so does that mean it cannot be wild? Also, as you can see below, it is surrounded by intensive agriculture - perhaps the reason by there are so few deer - so it is in itself an ‘island’ which might also explain why Ash has become so dominant.

“I think it is a wilderness, if you can have a small wilderness”

So is it Rewilded? Well, yes because whatever its constraints in terms of being bordered by fields and the sea, nature has been allowed to lead its evolution, and nature at scale. The resulting ‘jungle’ is not our doing. To caveat that slightly, since becoming an NNR, it has been managed more for our collective expectations of what is important for nature. As Ali Driver said in Episode 5, there is nothing wrong with that at all, we need a mix of approaches for nature to recover.

The mosses, lichen, fungi found throughout the reserve are abundant and diverse as are the insect fauna found above and below ground.

So, Rather than going any further, I will let you listen to the interviews about this and form your own judgement about the place, management and other aspects of the reserve. Tom revealed quite a lot of my own still limited understanding of the sector.

Whatever you think of it, it is an immensely important part of England, not just for its biodiversity, geomorphology, fossils (I haven’t even touched on these), and the profusion of different habitats - but also as a place of wilderness, of isolation and of literary inspiration. Check out John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant's Woman.

Do visit it, and when you do (as a friend once said) “Breathe deeply, tread lightly”, and enjoy.

From the air

The following is a short video of drone footage giving and idea of scale. It was taken early April 2021 and the birdsong was recorded in the reserve on the same day as the drone footage. This is only a small part of the NNR, giving you a real sense of scale.

I hope you like the photos and the interview. My thanks to Tom, Rob and particularly Donald for the many visits. Donald will appear in another podcast. My thanks to you for listening and looking - please sign up to my email list here, and add a comment below if you wish.

If there are any terms that you don’t understand, please do look at the FAQs and links or drop me a note and ask.